This project was included in the Cooper Hewitt's 2018 Showcase of Student Projects on Accessibility and Inclusion.

CONTEXT

Most of us know someone in their 90s; if we're lucky, maybe a handful. But what happens when that lifespan becomes the average rather than the outlier? What happens when we live to be 110, 120, or 130?

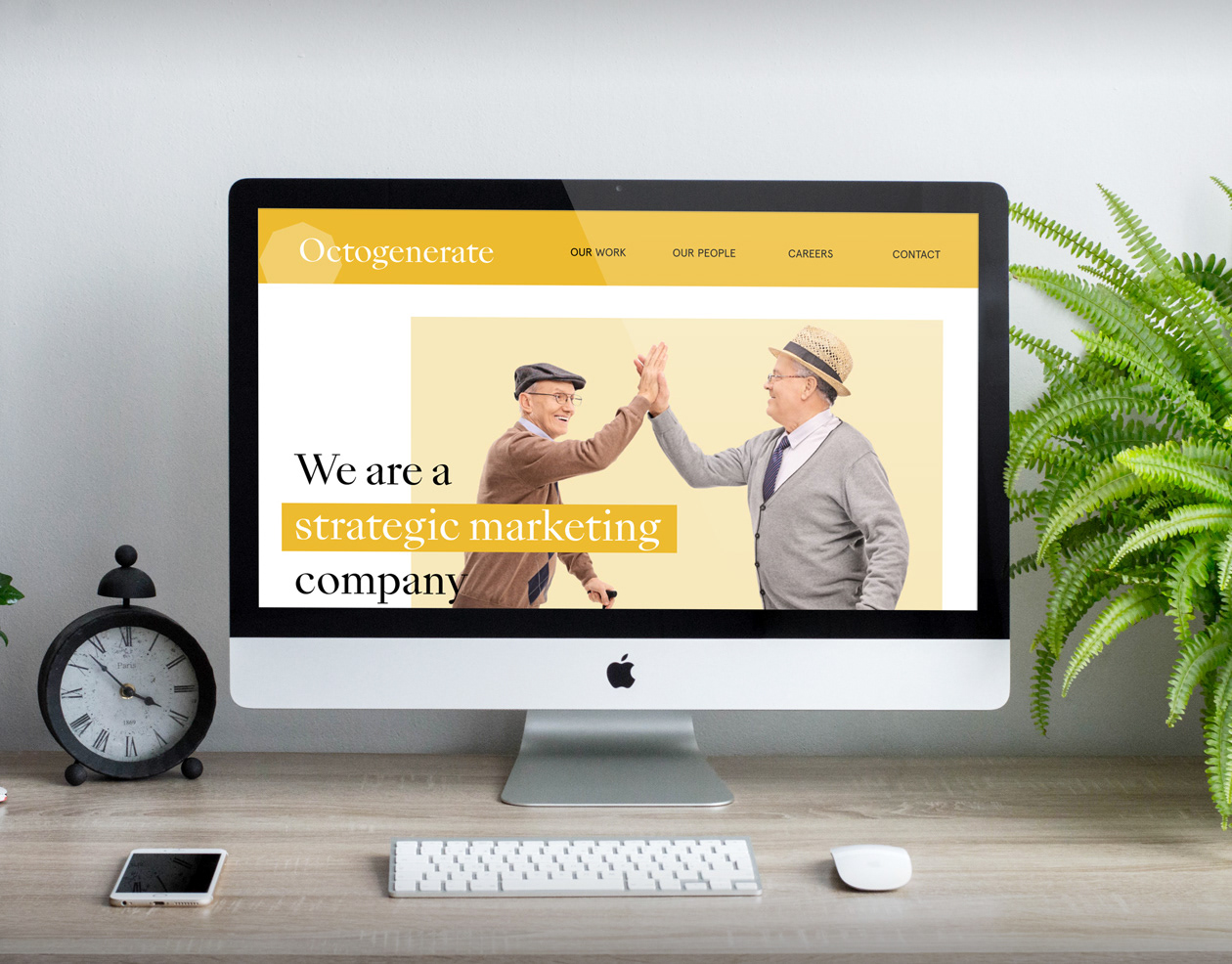

For this critical design project, I expanded upon the research collected for Octogenerate. I had gathered evidence that there was a disconnect between the ‘typical’ retirement age of 66, our increasing longevity, and our personal and societal financial realities. It seemed reasonable to suggest that people might be working longer, and later in their lives.

RESEARCH AND INSIGHTS

I conducted a number of interviews with so-called ‘aging’ professionals — those nearing or past the typical retirement age of 66. I asked about their relationship with work, past and present; their 5- and 10-year plans for working; their feelings about retirement; any particular strengths or weaknesses that they felt were age-related.

Almost every interviewee touched on two themes:

— They felt that they were doing the most meaningful work of their lives

— They knew of friends or associates in a variety of industries who had been unceremoniously forced into retirement

— They felt that they were doing the most meaningful work of their lives

— They knew of friends or associates in a variety of industries who had been unceremoniously forced into retirement

Going into this project, I had assumed that those most likely to experience to workplace ageism would be manual laborers, people whose physical fitness was necessary for success. I learned that white-collar professionals were just as susceptible: as one interviewee put it, “education doesn’t inoculate you from dispensability”.

PERSONA

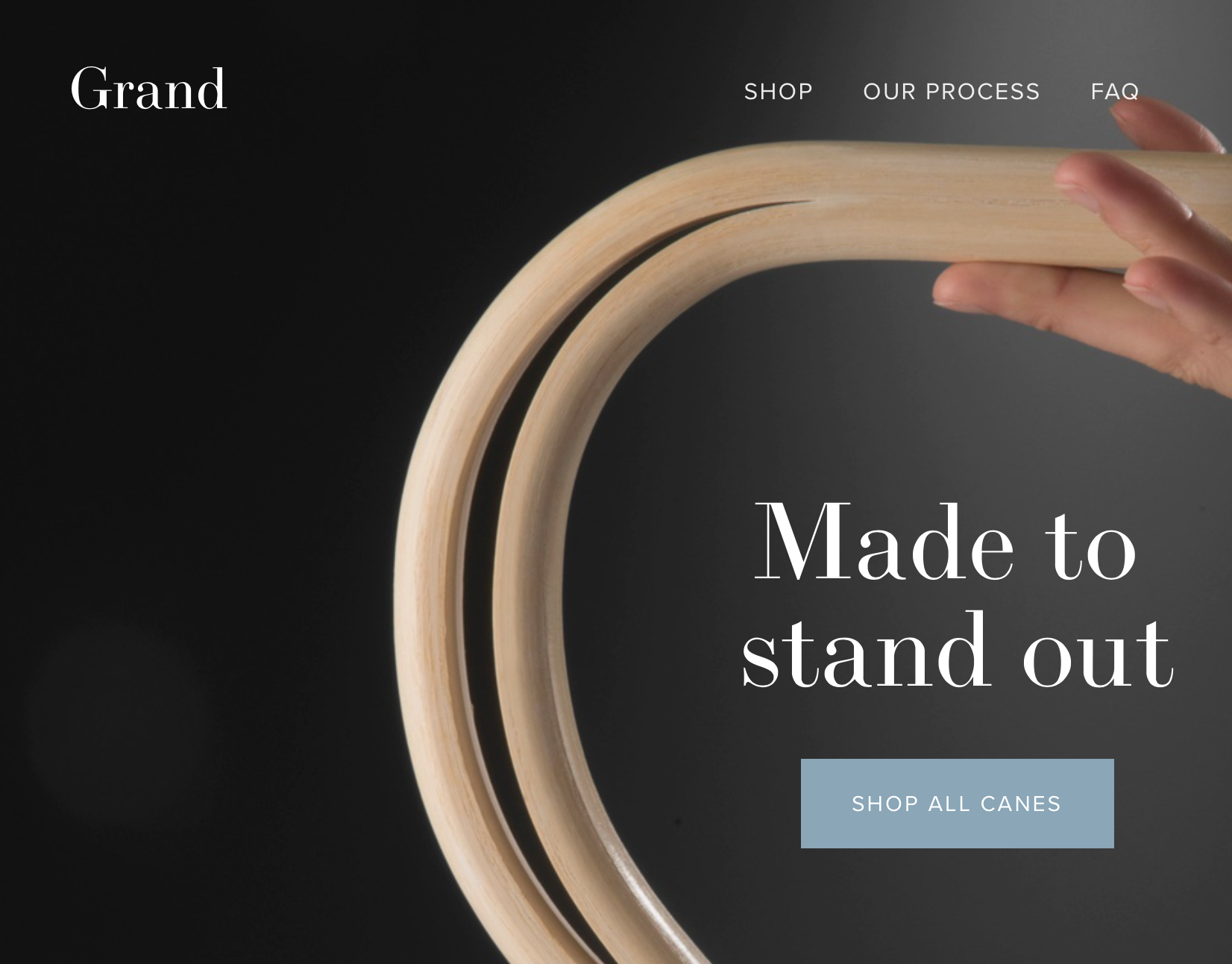

From the common themes of these interviews, I distilled a simple persona to guide the next phase of the project. This person is a white-collar professional, late 70s, cognitively sound but with bad knees. She is passionate about continuing to work. She recognizes her physical limitations — she needs a walker to help her safely get around — but can’t imagine entering, say, a boardroom with a typical tubular metal contraption. She wants something elegant that will fit in with her office’s modern décor.

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

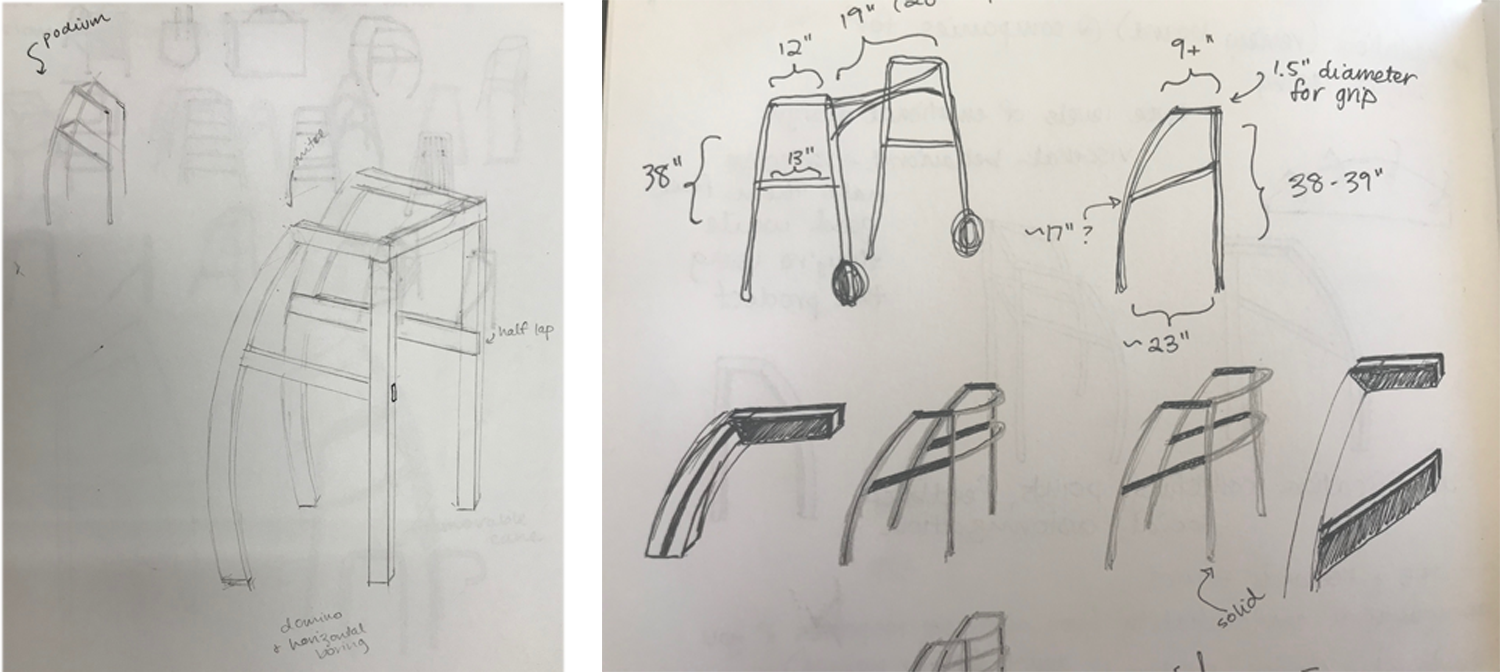

The medicalized aesthetic of current walkers suggest an all-encompassing infirmity. To counteract that aesthetic and what it represents, I took inspiration largely from handcrafted furniture. The mix of ash and walnut suggests a modern, high-end office. The form is reminiscent of a podium. And the gesture of the piece — one of forward motion — conveys pride and gravitas.

This is not a proposal for a functional product. A walker should probably be ergonomic, lightweight, and collapsible. Rather, it is a critical object that challenges our notions about aging, cognition, and dignity. It asks us to consider: what does — and can — a professional look like?

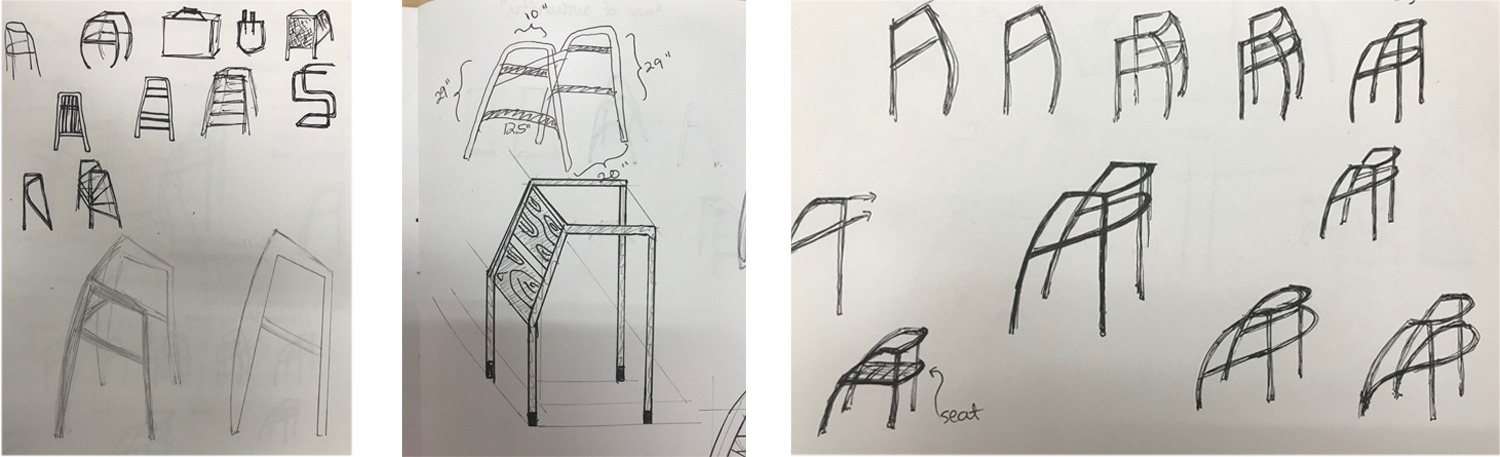

Balsa wood and cardboard sketch models.

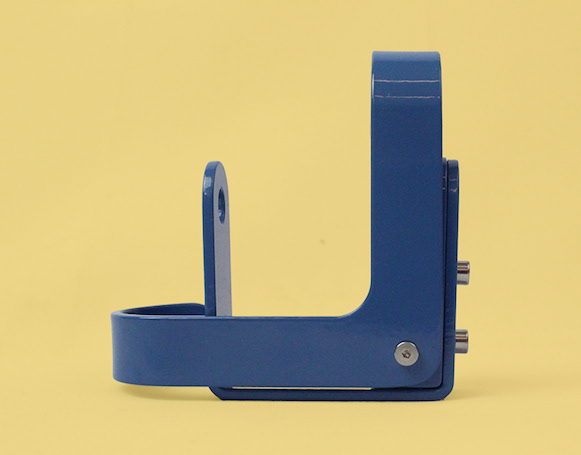

4/4" ash; milled walnut. The walnut accents feature the mirrored grain as displayed here.

Left: using a vacuum bag to laminate strips of ash. Right: laminating the handle pieces.

Left: defining the dimensions at scale. Center and right: all of the lap joints were cut at precise angles on a dado set.

Left: gluing the lap joints in place. Right: detail of lap joint after edges have been pin-routed.

Left: all jigs for bent laminations, horizontal boring, and DADO-ing lap joints on a curve. Right: detail of angled jig for horizontal boring machine.

Left: testing various router bits for the handle piece. Right: defining the placement of the stretchers.

Left: sanding. Right: finishing.